Article originally published in the Philadelphia Business Journal on January 21, 2020

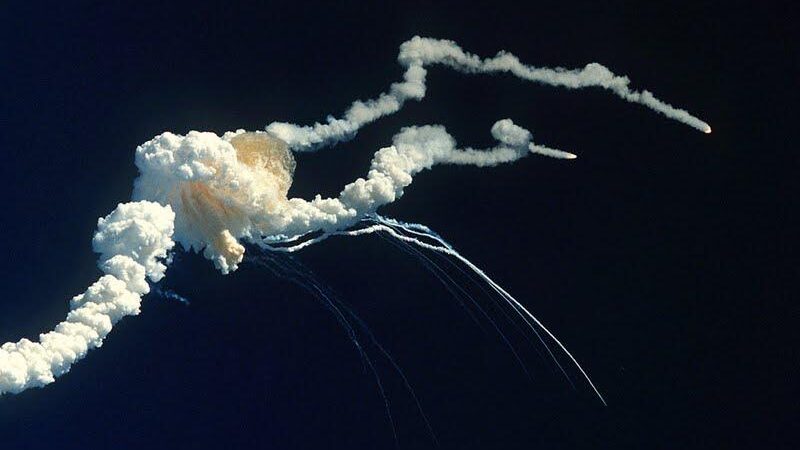

Tomorrow marks the 34th anniversary of the space shuttle Challenger disaster. On that date in 1986, Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff due to a leak in one of the O-rings of the solid rocket booster, resulting in the death of all seven crew members and the loss of the shuttle.

The leadership lessons taught by the decisions leading up to the Challenger disaster are so important that each year, I write an article to remind leaders about three valuable lessons taught by the Challenger tragedy — the importance for leaders to listen to their experts, face the brutal facts of reality, and don’t forge ahead to meet an important commitment when there is more than a remote probability that doing so could result in a catastrophe.

NASA had made unrealistic launch frequency commitments to Congress in order to secure increased funding for the space program. On Jan. 28, 1986, NASA risked a catastrophe — they ignored their experts and launched Challenger.

The engineers at Morton Thiokol — the contractor responsible for the design of the solid rocket boosters — were concerned about the effect of the cold weather on the solid rocket booster O-rings. The O-rings were designed by these engineers to operate at an ambient temperature of no less than 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

On the day of the launch, the ambient temperature was 30 degrees. Worried about the brittleness of the O-rings, Thiokol told NASA that the launch needed to be postponed.

NASA ignored the risk of an O-ring failure and objected to the recommendation to delay the launch. The launch had already been delayed a number of times for various reasons. One NASA manager is quoted as saying, “I am appalled by your recommendation.” Another NASA manager said, “My God, Thiokol, when do you want me to launch — next April?“

Thiokol management, facing pressure from NASA, eventually acquiesced and agreed that the launch could proceed. The rest is history: an O-ring failure caused the loss of Challenger and its crew.

What drives leaders to meet their commitments, a natural characteristic of all leaders, even though doing so may mean experiencing adverse consequences? They want to maintain their credibility with those who have power over them, to whom they have made commitments, regardless of the inadvisability of meeting those commitments.

In the case of NASA and the decision to launch Challenger, the space agency wanted to meet its commitment to Congress, which provided funding for the nation’s space program. For CEOs, it’s their board of directors, who can terminate them for not meeting their commitments, or their shareholders, who if dissatisfied with the financial performance of the company, can drive down the company’s stock price.

In his book, “The Challenge Culture: Why Most Successful Organizations Run on Pushback,” former chairman and CEO of Dunkin Brands Group Nigel Travis writes about the importance of establishing a challenge culture within organizations in which input from employees is welcomed by their leaders.

Travis writes that a challenge culture is one “in which direct reports can challenge their bosses … and colleagues can challenge each other… [so that] people have a say, where people understand what’s going on. The results are great business solutions and total buy-in, because people feel involved [and respected].”

Of course, that culture needs to focus on attacking business issues and not people, so that challenging others doesn’t destroy working relationships. Respecting civil discourse is a key determinant for success in a challenge culture.

Working in a challenge culture requires individuals with the self-confidence to hear criticism of their ideas and not take it personally, and to have the ability to challenge others. Leaders should create an environment and institutional culture that welcomes and encourages individuals to share their opinions.

A courageous independent thinker should feel comfortable voicing their opinion and try to convince everyone of the validity of the organization’s reality. The views of the independent thinker may not be ultimately adopted, but at a minimum, those views provide a different path, a path against which the majority opinion can be tested and either confirmed or changed. Under this type of process, the best decisions will emerge.

Business leaders, remember these lessons. It’s a strength to admit to your board that the current situation has caused you to change your mind and not fulfill a commitment that no longer makes sense in the current environment. It is a weakness to proceed as originally planned and possibly suffer a disastrous consequence.

In the words of renowned Brazilian novelist, Paulo Coelho, “If you want to be successful, you must respect one rule: Never lie to yourself.” Remember this when one of the independent thinkers on your staff reminds you to face the brutal facts of reality.

Stan Silverman is founder and CEO of Silverman Leadership and author of “Be Different! The Key to Business and Career Success.” He is also a speaker, advisor and widely read nationally syndicated columnist on leadership, entrepreneurship and corporate governance. He can be reached at Stan@SilvermanLeadership.com.