Article originally published in the Philadelphia Business Journals on March 9, 2020.

For the third time in the last 10 years, a Philadelphia nonprofit or governmental authority has been caught up in a scandal involving inappropriate behavior by a leader of that organization.

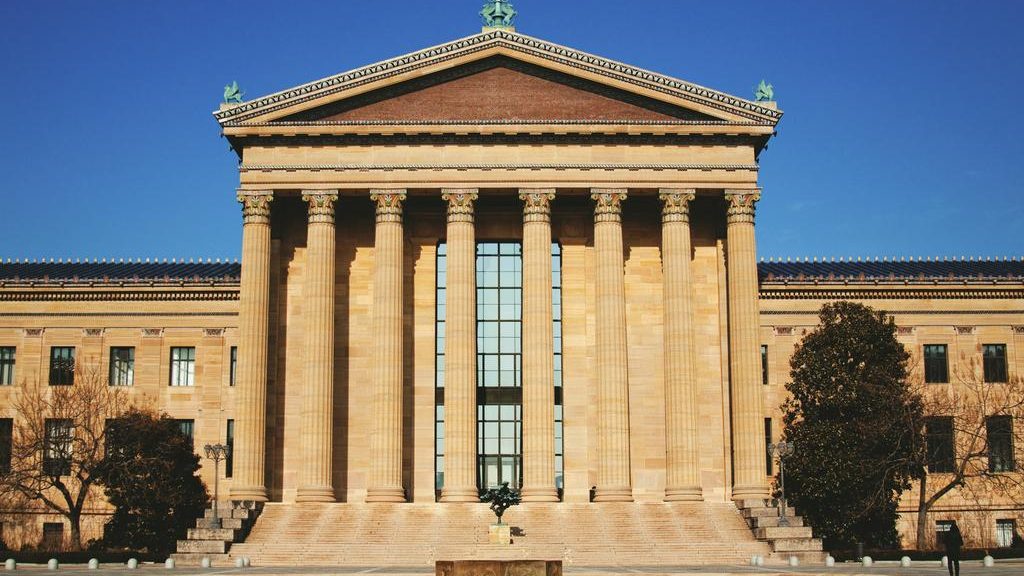

The most recent scandal occurred at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, when a number of female employees accused Joshua Helmer, a former assistant museum director, of making inappropriate advances and intimidating them with threatening comments, creating a toxic work environment.

The New York Times broke the story in a Jan. 10 article which reported that complaints about Helmer were made as far back as 2016, with no apparent intervention by museum leadership. In February 2018, Helmer resigned his position. Shortly after, he was hired to head the Erie Art Museum. Three days after the New York Times article and due to a similar complaint about him by an Erie Museum intern, Helmer left that position.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney, an ex-officio member of the board of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, commented, “PMA leadership should review and strengthen its policies regarding anti-fraternization and sexual harassment, and require training for all staff.”

The board has not installed an ethics hotline directly to the board audit committee so that complaints of misconduct could be investigated and acted upon if appropriate. At most public sector companies, this is a best governance practice. This is less common among nonprofits and government authorities, to their detriment.

Philadelphia Museum of Art CEO Timothy Rub apologized to museum employees at an all-staff meeting in late January for the “confidence he put in Helmer.” The Inquirer quoted museum staffer Sarah Shaw, stating, “I hoped for strong policy statements that empowered staff, like ‘This is how we will respond consistently to reports of harassment.’”

In February 2017, I wrote an article headlined, “Here’s what can happen when boards don’t adopt the best governance practices.” That article described scandals at the Philadelphia Parking Authority and the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

In September 2016, the board of the Philadelphia Parking Authority allowed its then-executive director, Vincent Fenerty, to keep his job after an investigation showed that he had sexually harassed an employee. The board reduced his personnel decision-making power, imposed other restrictions and made him pay the $30,000 charged by an outside investigator working on the case. He should have been fired.

Felicia Harris, president of Philadelphia Commission on Women, said, “[Fenerty’s] continued employment sends the message that sexual harassment is OK, and that the harm caused can be erased by monetary payment. Sexual harassment can’t be written off like a parking fine.”

Shortly after the decision by the Parking Authority to permit Fenerty to remain in his position, the board learned that he had sexually harassed another employee in 2006. Fenerty resigned the next day, knowing that this time the board would fire him.

It’s clear that the Parking Authority board did not learn from a similar 2010 scandal at the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

In that scandal, executive director Carl Greene settled four sexual harassment claims over five years by paying off the victims and not telling his board he was doing so. Greene faced similar accusations in the past, but he was hired anyway. Greene also faced a host of corruption accusations while at the PHA, which resulted in a federal investigation. He was subsequently fired.

Describing the culture within the PHA under Greene’s leadership as “toxic” is an understatement. Where was the board while all this was going on?

A core principle of board oversight is that boards are responsible for governance, not operations. Governance includes ensuring the CEO espouses an ethical tone at the top, nurtures the right culture and that the behavior of employees do not harm the reputation of the organization. This is why hotlines were mandated for public companies by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in the wake of the Enron, WorldCom and Tyco accounting scandals.

CEOs and boards of nonprofits and government authorities would be wise to adopt hotlines overseen by third-party providers, reporting to the audit committee of the board, that will take appropriate action when those reports are made. Employees will use hotlines to report financial and management wrongdoing as well as leaders who create a toxic work environment.

Lack of trust within organizations is an important issue with employees. It’s one of the reasons organizations lose good people. The level of trust between employees and the senior leadership team of an organization will significantly increase if the employees know they have a path to report wrongdoing to the board and have confidence that their allegations will be investigated. An ethics hotline is the best way for the board to protect the reputation of the organization.

Stan Silverman is founder and CEO of Silverman Leadership and author of “Be Different! The Key to Business and Career Success.” He is also a speaker, advisor and widely read nationally syndicated columnist on leadership, entrepreneurship and corporate governance. He can be reached at Stan@SilvermanLeadership.com.