Article published in the Philadelphia Business Journal on January 24, 2022.

Many of us remember with shock and disbelief the destruction of the Challenger space shuttle and the loss of its seven-member crew shortly after launch. Thursday is the 36th anniversary of that fateful day. Each anniversary, I write about the lessons learned from that disaster.

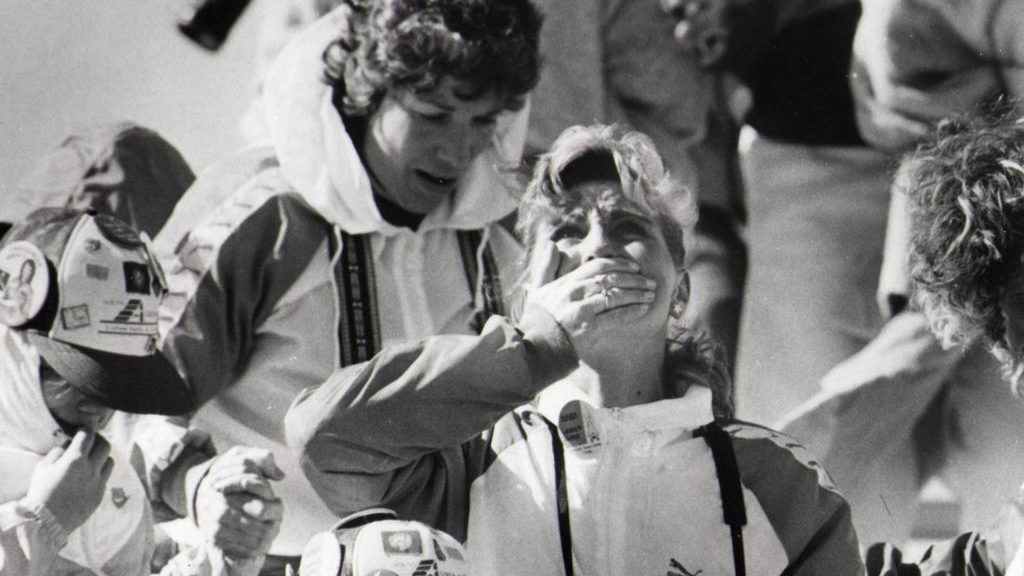

Challenger exploded on Jan. 28, 1986, 73 seconds after liftoff. The outside air temperature on launch day was 38 degrees Fahrenheit. The O-rings that sealed sections of the solid rocket boosters were designed for a temperature of no less than 53 degrees.

The low temperature would cause the O-rings to change from pliable to brittle, resulting in the possibility of fuel leakage and an explosion. This is what occurred. Ignoring the risk, NASA launched Challenger, which resulted in the loss of the shuttle and seven astronauts, including Christa McAuliffe, the first teacher in space.

What are the fundamental, timeless and important leadership lessons taught by the events leading up to the Challenger disaster? Failure to listen to the experts, an organizational culture that discouraged pushback and refusal to face the brutal facts of reality. This national tragedy should not have happened.

Listen to your experts

Worried about the temperature on launch day, the Morton-Thiokol engineers who designed the O-rings told NASA that the launch needed to be postponed.

The launch had already been delayed a number of times for various reasons. One NASA manager is quoted as saying, “I am appalled by your recommendation.” Another NASA manager said, “My God, Thiokol, when do you want me to launch – next April?

Thiokol management, facing significant pressure from NASA, eventually acquiesced and agreed that the launch could proceed, resulting in disastrous consequences.

The culture within NASA had been described as “we can achieve anything” arrogance. NASA had made unrealistic launch frequency commitments to Congress in order to secure increased funding for the space program. This drove the decision to ignore the experts – the Thiokol engineers – and launch Challenger in cold weather conditions.

In addition to the brittle nature of the O-rings, NASA senior leadership knew that O-ring erosion plagued previous shuttle launches. NASA was warned that “failure [of the O-rings] during launch would certainly be catastrophic.” However, due to their commitment to Congress, NASA continued their very aggressive launch schedule rather than suspend launches until the issue was fixed.

Many times a decision will come down to assessing the risk of various courses of action. When a particular course of action could be catastrophic, one should not take the risk. Unfortunately, the NASA decision makers who pushed for the Challenger launch did not think in these terms.

Establish a challenge culture that encourages pushback

In his book, “The challenge culture: Why most successful organizations run on pushback,” former chairman and CEO of Dunkin Brands Group Nigel Travis writes about the importance of establishing a challenge culture within organizations in which input from employees is welcomed by their leaders. This was not the culture that existed within NASA.

Travis writes that a challenge culture is one “in which direct reports can challenge their bosses … and colleagues can challenge each other… [so that] people have a say, where people understand what’s going on. The results are great business solutions and total buy-in because people feel involved [and respected].”

Of course, that culture needs to focus on attacking issues and not people, so that challenging others doesn’t destroy working relationships. Respecting civil discourse is a key determinant for success in a challenge culture.

Value the lone wolf who points out the brutal facts of reality

President Ronald Reagan established the Rogers Commission (named for its chairman William P. Rogers) to investigate the reasons for the Challenger disaster.

Physicist Richard Feynman was the lone wolf on the Commission. He was at odds with commission chairman Rogers on many issues during the investigation.

Feynman learned that the final Commission report would not focus on the brutal facts of reality he felt were key to the loss of Challenger. He decided to write a minority report. If it wasn’t for Feynman, these issues would not have surfaced.

In the words of renowned Brazilian novelist, Paulo Coelho, “If you want to be successful, you must respect one rule: Never lie to yourself.” Leaders, remember to listen to your experts, establish a challenge culture and value the lone wolf within your organization.

Stan Silverman is founder and CEO of Silverman Leadership and author of “Be Different! The Key to Business and Career Success.” He is also a speaker, advisor and widely read nationally syndicated columnist on leadership, entrepreneurship and corporate governance. He can be reached at Stan@SilvermanLeadership.com.